Mental Health Landscape

in Pakistan

A sneak peek

August 14, 2020

Mental health is a sensationalised topic across the globe. There is a lot of talk and debate. It is a leading discourse amongst politicians, healthcare professionals and influencers. All agree there are substantial opportunities for improvement but very few offer real solutions which are feasible within the political, socioeconomic, and healthcare infrastructure available. Working as a doctor in the UK, I have no doubt that mental health is a poorly funded and often neglected area even in the National Health Service (NHS). All too often a young teenager is denied the right help because “she is not anorexic enough.” I remember feeling very unsettled in my Intensive Care Unit rotation at the esteemed St Mary’s Hospital, one of London’s four major trauma centres. I naively associated trauma to be things like car accidents and adventure sport injuries. At St Mary’s I realised just how wrong I was. I felt the distress of a mother as she battled the decision of how much longer to keep her son on the ventilator after he tried to take his life by jumping in front of a tube (London’s underground train). My heart went out to a young 30-something year old who had stabbed himself in the neck, chest, and thigh amid a flare of his untreated schizophrenia. This is ALL avoidable trauma. It shouldn’t exist. If only they got help 10 steps before this point. Hello powers-that-be, surely its cheaper to fund for mental health in the community to prevent it reaching the point where you must fund over £500/night for an Intensive care bed?

In London, although there is a long way to go, there is a silver lining – people are talking about it and the taboo is slowly fading. In Pakistan, the gravity of the mental health landscape is even more serious. For there is no talk, there is only silence.

In fact, so deep is the silence that Pakistanis don’t even recognise mental symptoms as a medical problem. It builds and builds until it manifests as physical symptoms which they can explain – and hence finally recognise there is a problem. This is a process called somatisation and is common amongst children in the UK. How many times have we heard children saying they have “tummy pain” when they don’t want to go to school? Of course, they aren’t faking the tummy pain, it is real, but it is in response to a psychological stressor rather than an organic problem in their tummy itself. It is easier for a child to explain ‘tummy pain’ than the complexities of feeling low, anxious, or stressed. Interestingly, adults in Pakistan with depression and anxiety complain of predominantly somatic symptoms. “Paseena aata hai”/ I sweat a lot; “Haath kaanp te hain”/ hands tremble or shake; dil kamzor hai/ heart is weak; Per thande hain/ feet feel cold; ‘Sar bhari lagta hai’/ head feels heavy. Whether or not Pakistanis experience more physical symptoms compared to their western counterparts with a depressive illness is unclear, but what is clear is that as a population they communicate their emotional distress somatically rather than psychologically. I can only hypothesise why this is the case. Is the Pakistani culture more sympathetic to physical illnesses and therefore more accepting of physical descriptions of mental illnesses? Does Urdu not have the required vocabulary and terminologies to describe mental symptoms? I admit I had to google Urdu equivalent of “depression” which is apparently “Dimaghi dabao” – the literal translation of which is “pressure on the mind.” This urdu term I have heard being used seldomly. People just use the English word “depression” instead even when speaking Urdu. Or is it that Urdu simply just needs to catch-up? Afterall, depression historically meant an area lower than its surrounds in topography and wasn’t associated with mental psychology until the 19th century.

The intricacies of finances are woven in the mental health fabric of Pakistan. It cannot be disentangled. Pakistan’s healthcare service is primarily funded by pay of the point of use. There is no elaborate system of GPs and patients often directly make appointments with specialist doctors in the first instance. As we know that Pakistanis predominantly have somatic complaints of mental illnesses. These patients have already had a large amount of their pockets drained to visit the cardiologist for their chest pain or gastroenterologist for the abdominal pain and a whole series of normal scans and investigations that come with it to confirm they have no organic problem. Following the whole charade, they may finally be referred onto the psychiatrist at which they have to fish out even more cash if they have any left to spare. To add to the complexities of finances, there is a strong belief system in ‘Hakeems’ or ‘traditional healers’ and patients often turn to them first prior to formal psychiatric help – this means more money spent on help which may not be beneficial.

Mind Organisation

My first experience of Pakistan’s rural mental health came in the summer of 2019. I was a recently qualified doctor who had the opportunity given by Professor Saad Bashir Malik, an esteemed Consultant Psychiatrist in Pakistan, to shadow his charity MIND as they carried out their work in the villages of Punjab. We left Lahore with cars full of medications, two psychiatrists and a further two helping staff on a two-hour drive to Hafizabad, a rural village where MIND held its fortnightly clinics. As we emerged out of the car, I was amazed to see hundreds of patients already waiting for us. We should have had four psychiatrists on our team, but we were two down that week. I couldn’t fathom how our two brave psychiatrists could manage seeing all these patients?

The consulting room consisted of two desks, one for each doctor. One of the helping staff co-ordinated patients coming into the appointments whilst the other gave out the prescribed free medication. As the day went on, the orderly appointments fizzled, and patients clamoured to be seen in desperation so they can receive their free medications before our team left the village. Doctors had to battle through the cacophony to hear each patient in turn. Consultations were reduced to a single line “Has anything changed since our last visit?” and if the answer was “No” repeat prescription of the same medication was issued. This may be perceived as chaos to the western eye but what MIND has been doing is beyond incredible. Prior to MIND began their work in Hafizabad, potentially dangerous traditional practice of “blood-shedding” was widely used to as a treatment of mental illnesses whereby an incision was made in the patients’ forehead to let out the “contaminated blood.” Thanks to MIND, this is now uncommon, and patients turn to medical help provided by the organisation.

Punjab Institute of Mental Health

Pakistan has a serious shortage of psychiatrists. There are approximately 400 registered psychiatrists for a population of over 200 million. The gravity of such constrained resources was evident in the Punjab Institute of Mental Health (PIMH) in Lahore which provides care for patients primarily affected by schizophrenia or affective disorders. The largest in mental health facility in South Asia, it provides food, shelter, clothes, and medications free of charge to its resident patients. PIMH has a tremendous capacity of 1400 beds, over a century worth of history, its grandiose imposing Maharaja-style architecture and immacutely manicured lawns. At first glance, it may seem that PIMH is conducive for treatment of those with mental health conditions. Despite being situated in a bustling part of the city, tranquillity presides within the grounds of this asylum. But at closer look, the reality is that the system couldn’t be more outdated, psychiatric skills and resources significantly strained and an overwhelming poverty of empathy for the patients.

As we made our way inside the facility, we were dejected to see that the walls doors and floors of this ancient architecture had fallen victims to years of neglect. They were old, dilapidated and in desperate need of looking after. We went past the iron gates to general ward to meet and interview the doctors, nurses, and patients. The junior doctor we spoke to was stretched to a level much beyond a humanly capacity. They were thrown in the deep end and despite minimal formal training in psychiatry, they are frequently loaded with the responsibility of ward rounds and ongoing treatment decisions with no senior support. As many as 100 patients can be expected to be seen by only one doctor in the outpatient clinic. However, despite limited resources, the doctors did believe that with strong leadership and proper orientation of medical officers, patient care could be improved. I (naively) hope it does soon.

Nothing could have prepared me for the conversation with one of the patient residents diagnosed with schizophrenia. He had been living at PIMH for the last 10 years and I was confused as to why? He looked well and was definitely not experiencing an acute psychotic episode. He said he has been well for years. So, I asked him why he was still living at the facility? He began to reminisce and recount for us his poignant life story. He said his family dropped him at PIMH and never looked back. They refused to take him back, even he was well and it was upsetting to learn that this was not a unique story for him. Many of the patients there had been living there for decades as there was no safe place with a relative for them to be discharged. In his own words, patients are ‘orphaned’ as soon as they are admitted into the institute. In a culture where I though the value of the family unit was unbreakable, it was distressing to realise that when faced with a mental health issue, this strong family unit did not survive. So strong is the mental health taboo in Pakistan and change within general attitudes and perceptions of the Pakistani society towards psychiatric illnesses is slow. In fact, so slow is the changing attitude that despite the name being changed in 1996, it is still referred to by its original name as “Paagal Khana” or “Lunatic Asylum” amongst many locals.

I repeatedly questioned how PIMH still existed for over a century in a country where there is a serious lack of awareness of mental health conditions, lack of recognition that these may be treatable and the obvious lack of funds to support for the organisation. The answer was that in reality, PIMH is barely afloat. The initial 172 acres of its land is currently reduced to 52 and there were further talks about it losing its autonomy further by being taken over by another local general medical hospital. I agree that the concept of an “asylum” is rather outdated. Psychiatric patients should be treated and supported as much as possible in their homes and communities. However, it would be prudent to say that an asylum such as PIMH has outlived its role. It is the only hospital far and beyond which provides care for patients with psychiatric illnesses. It needs upgrading rather than dismantling. The inpatient structure where patients are confined to their hospital beds need to be transformed to allow more natural comfortable living environments with sitting rooms, television, gardens and communal spaces as you would see in UK’s general psychiatric wards. The concept of physical restraint needs replacing with high-quality nursing care which is governed by care and compassion. It should be a leading centre of psychiatric training of junior doctors. And I am confident with the right leadership, this could be possible.

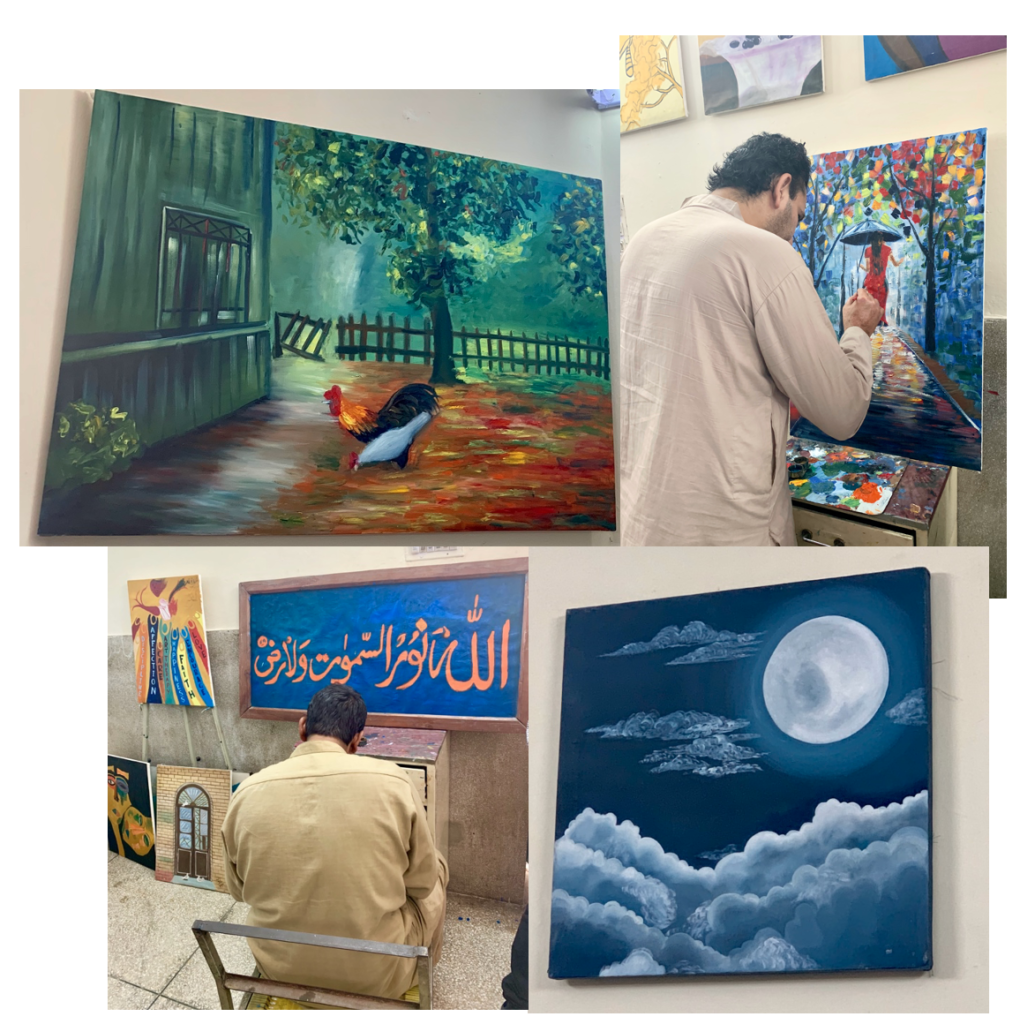

Our journey took us from the general psychiatry unit to the rehabilitation unit of the PIMH which put the biggest smile on my face. The lead consultants have developed a fun but rigorous programme to help integrate patients back into society and teach them to be self-sufficient. There is a whole range of activities on offer. A fully functioning gym and encouragement to engage in sports. There is tablet tennis and card games. Patients are also given the opportunity to learn and participate in other essential life skills such as cooking, tailoring and IT. There were hairdressing and barber facilities with the unit. The thing which struck me the most was the sheer creative talent which emanated from the patients and how the wonderfully they were provided with a safe platform and equipment to showcase these. They learnt how to paint from scratch. And the quality of these paintings speak for themselves.

It was heart-warming to hear them say the doctors and nurses have kept them like family. They laughed with us, shared their poetry with us and of course totally threw us off with their artistic talents! So far off from what the world outside the walls of the institute perceive them as?!

This is what we should aim for psychiatry care to be like. I understand it is hard to address the mental health issue in a population that denies its existence in the first place. The vast majority of the society ascribes supernatural causes to psychiatric illnesses such a curse, spell or a test from God. Prayer is often used to heal these patients and if that fails, the natural consequence is either physical restraint or abandonment. We need start talking about it and normalising it as a condition that can be treated. We Pakistanis have a lot of sympathy for patients with a “heart attack” or “Sugar” (Pakistan’s colloquial term for diabetes) or “Bukhaar (fever)” but very little for anxiety, depression and schizophrenia. Patients and psychiatry healthcare professionals both deserve dignity and respect. Referring to them as “Paagal (mad)” or “Paagalon ka doctor khud paagal ho jae ga (A madperson’s doctor would go mad himself)” is just not going to cut it. Terminology can shape attitudes, and we need to sanction these terms as a matter urgency. Pakistan’s current youth is a charged generation living amongst a changing time fighting the political status quo, corruption, women empowerment, and girl’s education. They are fed up with the lack of job opportunities. They are used to speaking out and change. They need to speak out against this mental health taboo and their message should reach out. Pakistan’s media is the strongest it has been. We need to use it to our advantage rather than against it.

When I used my social media facebook page to post (with permission) some of the painting of these patients, I got an overwhelmingly positive response. My friends and family were awed by their talents; they couldn’t believe psychiatric patients could be capable of that. But the comment which struck me the most was “You went to the mental asylum, did you not feel scared?” These patients are people, so why should I be scared to meet other people? The notion that psychiatric patients are violent and need to be chained strongly permeates through the very being of society. And I feel many will be willing to learn but there are very few people to provide them with the insight necessary. It is all our responsibilities to learn and to educate and start cracking down this mental health taboo for good.